Passing Shmassing

When I first heard the story of what happened to my great-aunt Lou (short for Louise), I remember even as a six-year-old feeling shocked, and so sad for her.

Growing up, my father would tell me how much he hated living in the backwoods of Morrow, Louisiana — so much so that he would regularly attempt to runaway. My grandfather, Louis, though everyone called him “Sonny” farmed cotton, and he made all of his ten children pick the cotton — painful work none of them wanted to do. Stories about Sonny from my aunts and uncles were that he was a cruel ladies man; with families all over town. My father wanted to be a scientist, and he knew the only way that could happen was if he escaped the house he was born in.

A town divided to this day, Morrow, population 686, is split by the US Route 71, and the railroad tracks that run through it. Blacks live on one side of the tracks and whites on the other. The post office was opened in 1883, but the school closed in 2009 due to a lack of students.

After many failed escape attempts, my father, Lawrence, was given a chance at education when Sonny and Agnes allowed him to live with his Aunt Lou, my grandmother Agnes’ sister.

Agnes and Lou’s story, like the stories of so many black people in the US, is somewhat of a mystery. My father told me that the women had escaped with their mother, my great-grandmother, “Chuk,” from a reservation in Oklahoma, following a beating by their father, a Cherokee Indian whose name no one knows. “Chuk” left with Agnes and Lou, and eventually married another man named “Energy Ford.”

Agnes married Sonny, and Lou remained unmarried.

Lou worked in an antique shop, and by Louisiana standards did pretty well. Her only request for my father, in exchange for living with her was that he worked, and that he become a Catholic; and for that she would pay for him to be educated (in Catholic schools only) through college.

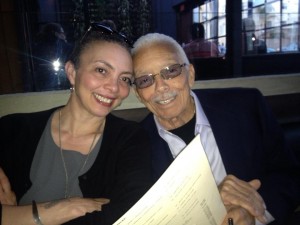

My father shined shoes, and ran dresses to and from the cleaners for the local house of prostitution. He says he never made it into the house, but caught a few peaks through the crack in the door now and then. My father would take “getting an education” all the way from Xavier University undergrad to the University of Chicago for a PhD in microbiology and fellowships at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, and Pasteur in France. Today, he works at University California, San Diego — still — at 84-years-young.

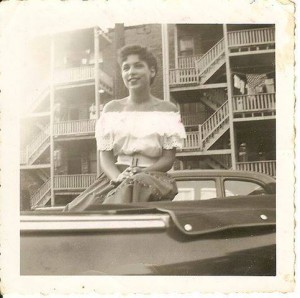

As a young man, my father and Aunt Lou would travel into New Orleans, for supplies for the store, and when they did, Lou insisted they sit at the front of the trolley — with ‘the other white people.’ My father says he lived in terror they’d get caught one day. Lou looked white. She had very pale skin and blue eyes. My father is very light, with wavy hair, a kind of young Harry Belafonte, with a bit more cream added. Lou would tell him, as my grandmother, Agnes said to me when I was a little girl, “I’m not a niggah. My husband is, but I’m not.” The family accepted that Aunt Lou “passed,” and that had my father been darker, she never would have taken him in, and he may never have become Dr. Alfred.

The day my father and I flew to Texas for a family reunion, and my uncle, Robert, picked us up from the airport, was the first time I ever saw my father cry. Aunt Lou had been minding the store, when two black men came in and robbed her. For some reason, no one understood why, the men shot Aunt Lou, and killed her. The men were arrested, but when the police asked why they shot her, my Uncle Robert told us they’d said, “we thought she was an old white woman.”

My great-aunt Lou had “passed” for white her whole life. My uncle, John, who is gay, passes for white and lives a closeted life today in Kentucky. He tells people he’s Brazilian.

I choose to embrace the “one drop rule” — legislated by Southern Jim Crow laws in the the late 19th and early 20th centuries to keep blacks from trying to “pass” for white. My father is more than a few drops black, and my mother was Jewish and British. I could pass for white, but I love being who I am. I identify myself as multicultural. I’m a gumbo stew with matzoh balls bobbling in the broth.

“Passing” has a sad history in my family, and I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. Having to live a lie to be who you are is something we should all be ready to move past.