Shmy Way or the Sweatshop

People who know me know that I’m somewhat obsessed with all things Indian. I travelled to Delhi, Agra, and Jaipur, and can hardly wait to return to explore different regions of the country. I read books about the culture, tried to learn a little Hindi, love the food. If the movies Slumdog Millionaire, Gandhi, or Water pop up on TV I can’t stop myself from watching—even though I’ve seen them countless times. I don’t know why the Indian subcontinent it holds such fascination for me, but it does. Perhaps in my previous life I was Indian. Who knows?

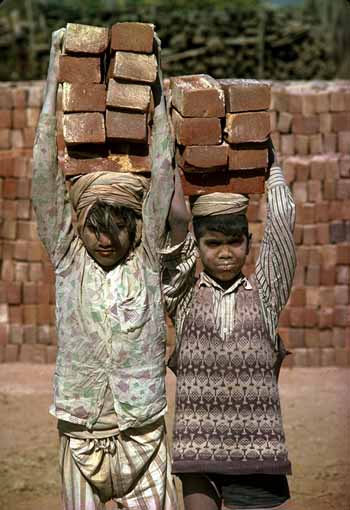

So, the question is: how would my shopping habits change knowing that so many products are made in sweatshops in places like India, where the working conditions are horrible, and children are often employed to make all the wonderful stuff that I covet?

While liberal Americans like me cry foul over third world conditions, the notion of the sweatshop was actually born in anti-bellum New York, the center of the nation’s garment industry, with workers in sweatshops making clothes for slaves on Southern plantations.

Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, most Americans made their own clothes at home. If people were wealthy, they were able to purchase “tailor-made” clothes. Tailoring was an immigrant profession. You didn’t have to speak English. If you could sew, you could work. You could support your family—that was the “opportunity” in the whole Land of Opportunity concept that was America in those days.

As the century turned, and the tide of Irish, Poles, Italians, and Jews continued to flood into America’s ports, the new immigrants took whatever jobs were available. “If the average American woman is the best-dressed woman in the world; the Russian Jew has had a good deal to do with making her one,” said Abraham Cahan, a Lithuanian-born American newspaper editor, novelist, and politician.

In 1910, nearly 70% of all women’s clothing and 40% of men’s clothing sold in the United States was produced in the garment district in New York.

The decline of the industry began in the seventies and eighties. Rents in the garment district increased, American workers were unionized and expensive. An over-seas workforce was a cheaper alternative. So began “outsourcing.” Today, 97% of clothes sold in the US are made in other countries.

With manufacturing moving out of the country, so did the monitoring of how employees are treated. A US Labor department lists more than 80 countries that employ child or forced labor. The list is alphabetical, beginning with Argentina and ending with Uzbekistan. The products include cotton, garments, gold, sugar cane, tobacco, coffee, leather, electronics… and even pornography.

So what to do?

Buy clothes at American Apparel? I’ve never shopped there, but I’m beginning to think that maybe it isn’t such a bad idea. Everything in the store is made in Los Angeles. The company supports immigration and health care reform and Prop 8. The cotton is organic. They pay their workers well, offer on-site medical facilities, and give health care. The only problem–the CEO Dov Charney and his penchant for sexually harassing and wrongfully terminating his female employees. Making it hard for me to support this company despite the “made in the US” label.

Reduce the amount of new clothes that you buy. Probably the easiest thing you can do. Simply purchase less clothing. Most of us don’t need or wear all of the clothes in our closet, so if we can curb the impulse to purchase another new piece of clothing, we don’t even need to worry about the issue of supporting sweatshops.

Stay out of department stores, especially big ones. Much of what is sold there is produced overseas, probably in sweatshops. If you don’t see “made in the US” on the label, it’s safe to assume the product was produced in a sweatshop.

Shop online and look for retailers that make a commitment to using fair labor practices. One website that I found helpful was sweatfree.org. Check out the “shopping with a conscience” consumer guide.

As it turns out, in India, the country I love so much, a 14 year old can begin to legally work. But nearly 22 million Indian children under 14 are forced to work. Fifteen million kids are sold into slavery every day. Think of that the next time you see that six hundred dollar pair of boots you just have to have. Think to yourself: How many months could an Indian family live on $600, and how old was the tike that stiched them together?